1.1.3. Curse of dimensionality

Overfitting is particularly prevalent in models that have a large number of parameters. Let’s use p to denote the number of parameters in our model. When p is large, the gap between training and test errors widens. This is often referred to as the “curse of dimensionality.” When we have the luxury to tweak more parameters to fit a limited dataset, we run the risk of fitting the noise instead of the signal.

To elucidate the concept of the curse of dimensionality, let’s begin by considering a classification task, in which we aim to distinguish between images of puppies and cats. Let the feature vector x denotes the pixel values.

One-Nearest-Neighbor (1NN):

In the 1NN classification rule, for each data point in the training set, the closest data point is selected as the prototype for its class. This means that a new data point is classified based on its proximity to the nearest neighbor in the training set.

Apparently, 1NN achieves zero training error: every image in the training set is matched with itself, ensuring perfect classification. However, this doesn’t necessarily translate to outstanding performance on unseen test images.

Interestingly, the complexity of the 1NN classifier is defined solely by n (the sample size), irrespective of the feature x’s dimensionality. Given that the sample size n represents the upper bound for a model’s complexity, 1NN is susceptible to the curse of dimensionality.

Impact of Dimensionality on Linear Classifiers:

To further illustrate the curse of dimensionality, let’s examine its impact on the performance of linear classifiers. Again, consider the puppies vs cat classification task.

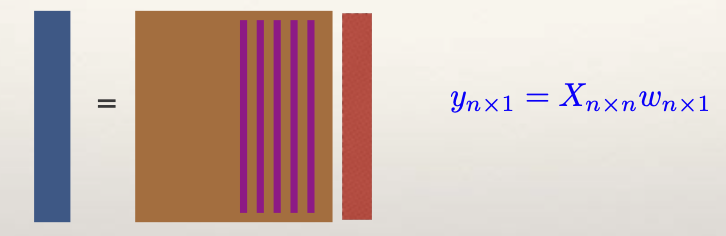

Likely, we can not find a linear function to seperate the two groups of images. However, by artificially increasing the dimensions – through the addition of random elements to the feature vector x - separation of the two groups becomes mathematically simpler. Let’s assume y is labeled as 1 or 0. As p (the dimension of x , taking into account the added random noise features) approaches n, we can always find a coefficient vector w to satisfy the equation below; that is, this linear function \(f(x; w) = x^t w\) can yield perfect prediction on the n training samples.

Learning from data is challenging because we typically have access only to training data. However, it’s essential to focus on minimizing test error rather than just training error. In the next discussion, we will explore the sources of test error and strategies for achieving the best tradeoff among them.